- Published on

What exactly is digital peacebuilding, and how does it differ from conventional peacebuilding efforts? This section dissects the concept, elucidating the role of technology in mitigating conflicts, fostering cooperation, and building sustainable peace. We explore the intersection of cybersecurity, digital diplomacy, and data-driven strategies in the pursuit of global stability.

Digital peacebuilding is the analysis of & response to online conflict dynamics & the harnessing of digital tools to amplify peacebuilding outcomes (Alliance for Peacebuilding).

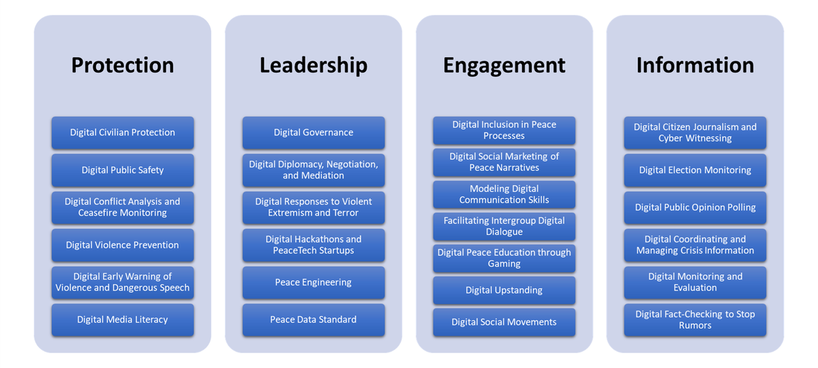

Digital peacebuilding is an emerging field at the intersection of technology, conflict resolution, and global stability. As outlined in Lisa Schirch’s report from the Toda Institute, this approach spans 25 spheres. These spheres encompass a wide range of strategies and initiatives that leverage digital tools and platforms to mitigate conflicts, foster cooperation, and build sustainable peace. From digital citizen journalism to peace engineering, this paper provides an overview of the diverse landscape of digital peacebuilding and its potential to reshape the way we address global conflicts.

In an increasingly interconnected world, technology has become a powerful force for both conflict and peace. Digital peacebuilding represents a paradigm shift in how we approach conflict resolution and the promotion of peace. It encompasses a vast array of strategies and initiatives that leverage digital tools, data, and communication platforms to address conflicts, prevent violence, and build lasting peace.

The category below puts digital peacebuilding into 25 distinct spheres, each representing a unique facet of this evolving field. These spheres offer insights into how technology is harnessed to analyze conflict dynamics, facilitate diplomacy, empower individuals, and promote responsible digital behavior. By examining these spheres, we gain a deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of digital peacebuilding and its potential to transform global stability efforts.

- Digital Citizen Journalism and Cyber Witnessing: Empowering individuals to report and document events and conflicts using digital platforms, helping to raise awareness and hold accountable those involved.

- Digital Conflict Analysis and Ceasefire Monitoring: Using digital tools to analyze conflict dynamics, track ceasefire violations, and gather data for conflict resolution efforts.

- Digital Election Monitoring: Leveraging technology to monitor elections, ensure transparency, and report any irregularities, promoting fair and peaceful elections.

- Digital Early Warning of Violence and Dangerous Speech: Utilizing digital tools to detect early signs of violence or harmful rhetoric, enabling preventive actions.

- Digital Civilian Protection: Employing digital means to protect civilians in conflict zones, such as providing early warnings or safe communication channels.

- Digital Public Safety: Using digital tools and infrastructure to enhance public safety and emergency response in conflict and crisis situations.

- Digital Public Opinion Polling: Conducting surveys and collecting public opinions using digital methods, which can inform decision-making and policy development.

- Digital Coordinating and Managing Crisis Information: Using digital platforms to efficiently coordinate responses during crises and manage information flows.

- Digital Monitoring and Evaluation: Using digital platforms to monitor and evaluate peacebuilding programs, improving their effectiveness and impact.

- Digital Fact-Checking to Stop Rumors: Verifying information and debunking false rumors or misleading content circulated online to prevent escalation of conflicts.

- Digital Governance: Enhancing governance processes through digital tools, increasing transparency, and citizen engagement in decision-making.

- Digital Diplomacy, Negotiation, and Mediation: Conducting diplomatic and negotiation processes through digital channels, including peace talks and conflict resolution.

- Digital Inclusion in Peace Processes: Ensuring that marginalized or underrepresented groups have a voice and participation in digital peacebuilding efforts.

- Digital Responses to Violent Extremism and Terror: Employing digital strategies to counter and prevent radicalization and terrorism online.

- Digital Social Marketing of Peace Narratives: Promoting peace and reconciliation messages through digital marketing and storytelling techniques.

- Modeling Digital Communication Skills: Teaching individuals how to effectively communicate and engage in digital spaces, fostering constructive dialogue.

- Facilitating Intergroup Digital Dialogue: Creating digital platforms for dialogue between different groups to bridge divides and build understanding.

- Digital Peace Education through Gaming: Using digital games and simulations as educational tools to teach conflict resolution, empathy, and peacebuilding.

- Digital Upstanding: Encouraging individuals to take a stand against online harassment, hate speech, and cyberbullying, promoting digital civility.

- Digital Media Literacy: Educating individuals on how to critically assess and navigate digital media, promoting responsible consumption of information.

- Digital Social Movements: Using digital platforms to mobilize and organize social movements focused on peace, justice, and human rights.

- Digital Hackathons and PeaceTech Startups: Hosting digital hackathons to develop innovative tech solutions for peacebuilding and supporting peace-focused startup initiatives.

- Peace Engineering: Applying engineering principles and technology to address peace and conflict challenges, such as infrastructure development in post-conflict areas.

- Peace Data Standard: Establishing data standards and protocols for collecting, sharing, and analyzing peace-related data.

I find it is helpful to reorganize them into four main categories.

- Information

- Engagement

- Protection

- Leadership

Digital peacebuilding represents a dynamic and evolving field that harnesses the power of technology for global stability and peace. These 25 spheres of digital peacebuilding demonstrate the breadth and depth of initiatives aimed at addressing conflicts and promoting cooperation. As technology continues to advance, so too will the potential for innovative digital solutions to shape the future of peacebuilding efforts. By exploring these spheres, we gain valuable insights into the transformative potential of digital tools in the pursuit of a more peaceful world.